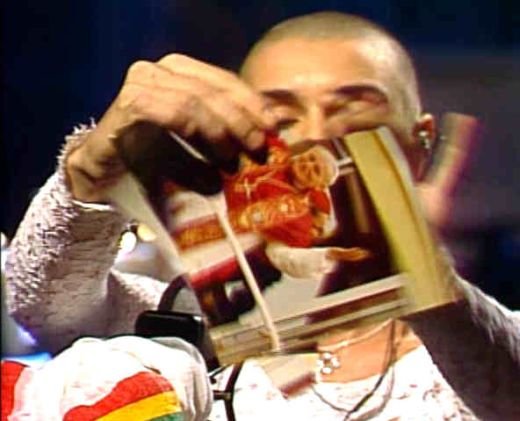

On October 3, 1992, Sinéad O’Connor tore a picture of Pope John Paul II into pieces after performing a rendition of “War” by Bob Marley on Saturday Night Live. In 1992, I was not alive. My parents would meet about a year and a half later—both raised in New Jersey in Catholic families—getting baptized, receiving communion, and getting confirmed. My father was an alter-boy, going to the church on his lunch breaks at school to help with mass during the week. (He was always agnostic, but he played his part in the ritual).

I grew up vaguely Catholic. I was baptized, went to CCD, and right before my First Communion, my Jersey-Italian mother with a correspondingly strict Catholic upbringing pulled me out of the Catholic Church in favor of a church under the Presbyterian denomination. I was happy to be freed from sitting for hours weekly in an old classroom that smelt like dust and had crucifixes of a nearly naked, bleeding, emaciated Jesus hanging from the walls. I made my first communion casually, without a white dress or formalities. I lined up in the sanctuary and ate a little cracker and drank a little wine (grape juice, probably) and walked back to the pew, my mom with tears in her eyes, likely because of the importance of the first communion in her upbringing, which I didn’t understand at the time. I thought it was just prayer with snack.

Even though Sinéad O’Connor ripped up that photo nearly four years before I was born, I remember the controversy still present in my family when I was young. Her name was spoken in hushed tones, and I don't think I had ever even heard her sing. It felt sacrilegious to even mention her in conversation. As a child, I never knew what she had done, but I knew it had to be something horrible—something so wretched it rendered her name unspeakable. I grew up making assumptions based on silence and hushed conversations, like many children do.

On October 3, 1992, Sinéad O’Connor tore a picture of the Pope into pieces to protest child sexual abuse in the Catholic Church. This was nine years prior to Pope John Paul II publicly acknowledging the abuse within the Church—a now commonly recognized issue, and even the butt of jokes by many mainstream comedians. But O’Connor, a pop singer and a survivor of abuse herself, was blacklisted by the media (and in turn, by many Catholic families like mine) for speaking the hard, vile truth. She was not acting how a pop princess with doe-eyes and a pretty face should act. And her resistance was punished.

Sinéad O’Connor’s death was announced this past Wednesday. Upon her death, I had never heard a song of hers—maybe a part “Nothing Compares 2 U” on the radio. (I know this might seem unexpected from me based on the other musicians and bands I listen to: i.e. The Cranberries, Kate Bush, PJ Harvey, Alanis Morissette, 4 Non Blondes, etc.) I never explored her music because I always thought that she had truly done something horrible. Reading the articles about her postmortem, I realize that her major controversy is that she was brave enough to call out child sexual abuse within the Catholic Church. To think that this person was blacklisted by the media, booed at public events, left without support by other entertainers (not you, Kris Kristofferson), and made out to be the villain because she was advocating for the safety of children is beyond contemptible.

On Thursday, I put on The Lion and the Cobra, Sinéad’s debut album. The 1987 album is named after Psalm 91. I am immediately met with regret. “Jackie” starts the record—her voice rings like a siren and I have chills down my legs. The album continues, exploring relationships and sexuality, society and injustice, and religion all while maintaining radio-friendly musicianship. I feel nauseous because I missed out on loving her and her music while she was still alive.

For He will give His angels orders concerning you, To protect you in all your ways. On their hands they will lift you up, So that you do not strike your foot against a stone. You will walk upon the lion and cobra, You will trample the young lion and the serpent.

—Psalm 91:11-13

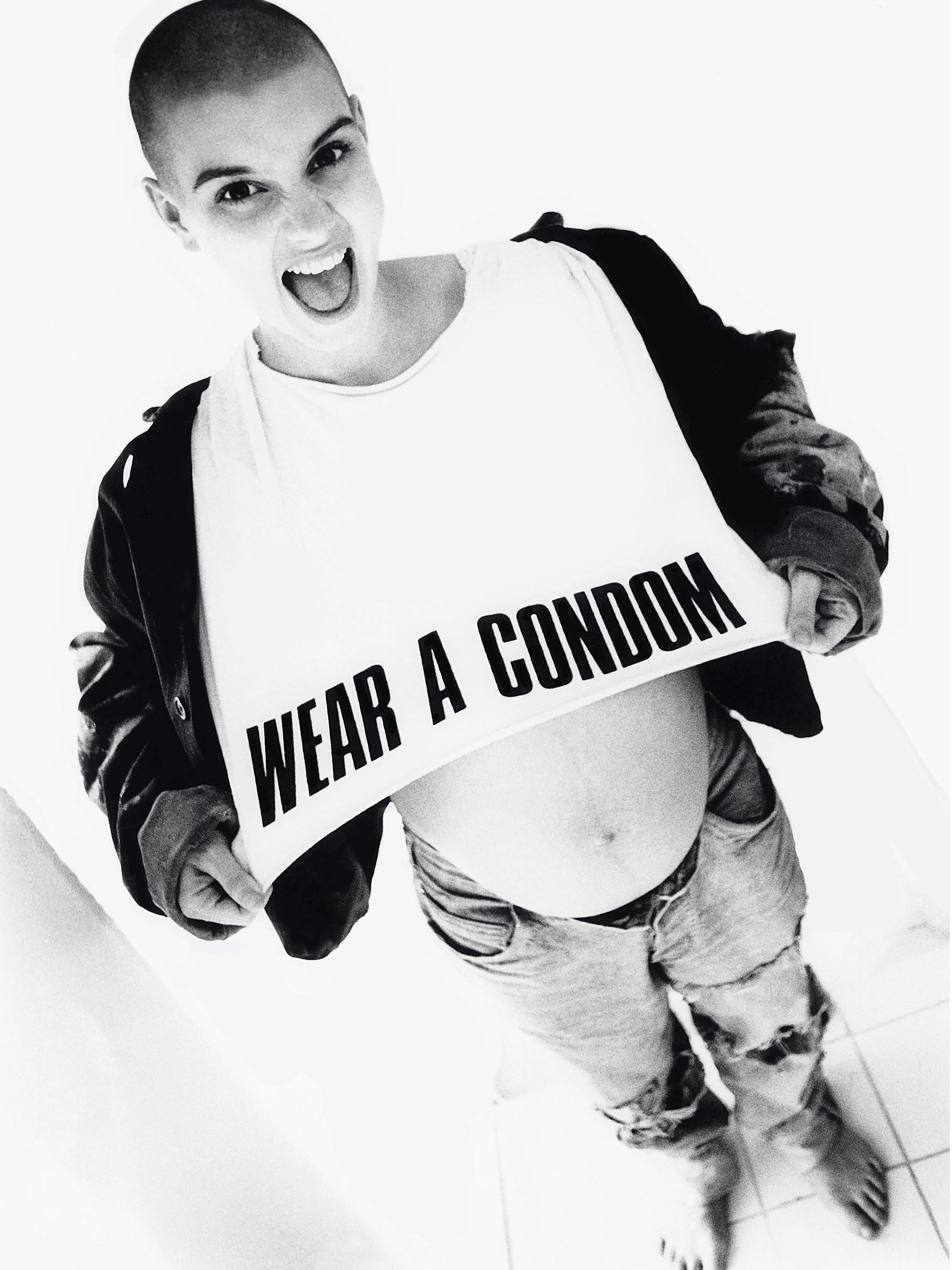

I see myself in Sinéad—except I’m far less brave. I wish I could say I am as brave as her, but a lot of the time I get so anxious at the prospect of being perceived that I am frozen in fear. I don’t even know if I could perform one of my songs on SNL, let alone protest arguably the most powerful institution in the world when the cards are so obviously stacked against you. But we both are queer artists, musicians, lyricists, and writers with fibromyalgia, borderline personality disorder, agoraphobia, and misdiagnoses of bipolar disorder.

Early last year, her son Shane passed away due to suicide. I don’t mean to speculate on the cause of her death (which has been unannounced), but I know based on my family’s own experience that suicide within the family is something you never really recover from. My two uncles (my father’s older and younger brothers) both committed suicide. Todd died in 2014, the day after his father was buried. Keith died in 2018. Both had multiple attempts, and none of them were easy on our family or close family friends. We tried at support, at rehabilitation, at recovery—but ultimately, it was futile. None of us were ever the same afterwards.

“You praise her now ONLY because it is too late. You hadn’t the guts to support her when she was alive and she was looking for you.”

Sinéad, I’m sorry. I am so sorry. The world owes you an apology, and I’m sorry that you could not witness that in this lifetime. The media led a campaign against you, egging on the public to crucify you for doing what a true artist does: being a conduit for the unadulterated truth, no matter how uncomfortable it makes the audience.

So many women are revered in death after living a life of shrouded in criticism and condemnation. This isn’t a new phenomenon. Amy Winehouse, Whitney Houston, Tina Turner, Billie Holiday, Nina Simone, Britney Spears—the list goes on. The media are way more than complicit; they are a huge, if not the main, reason that we see lives and reputations destroyed until it is tragically too late. Then upon death, like the flip of a switch, we see the media completely change its tune. The very people who wrote the articles perpetuating the narratives that turned these women into villains and pariahs are now the people writing eulogies and in memoriam think-pieces for clicks and ad revenue on their websites.

Sinéad deserved better. Artists do not have to be tortured to be artists. As consumers of media, we have the ability and a responsibility to think critically, practice media literacy, reject dangerous narratives, and stop torturing artists. It is a privilege to witness art. Artists deserve better.